How do music genres shape inequalities and spacial dynamics in nightclubs?

Two recent papers by Timo Koren, PhD and researcher and lecturer at Erasmus University, contribute valuable insights to nighttime research on how music genres shape social and spatial dynamics and inequalities of nightclubs. This research expands on established nighttime research topics of identity formation and regulation, viewing nightlife through the lens of cultural production. Using case studies of niche EDM and eclectic clubs in Amsterdam in 2019, it examines the ways in which the cultural production and economic organisation of club nights at genre-specific venues impact the gendered meanings and racial inscriptions of genres.

Here, the cultural production of the genre is the process of programming and organising club nights in niche EDM (styles outside mainstream EDM) and eclectic (mix of genres including r&b, pop, hip hop and dancehall) venues. Cultural production produces social and cultural meaning, and economic conditions can lead to inequalities in labour and public participation. Genre is understood not only as a descriptive label, but also as a set of orientations, expectations, and conventions coming together to produce a certain kind of music. Within genres, norms, standards and geographies are not fixed and can change based on social, cultural and economic interactions.

What causes gender inequalities in the cultural sector? Does this differ along genre lines? How is meaning assigned to gender in different genres? Existing research shows that gender inequalities in nightlife employment are a consequence of informal work cultures’ privileging of male labor, including closed social networks and sexist perceptions and stereotypes within the production of the genre.

This study uncovers new and localised debates. Genre cultures are influenced by public critique and political discourses on gender equality and exclusion, manifesting here in observed discussions on gender parity in line-ups and employment in niche EDM spaces. Efforts for gender parity and diversity are encouraged by these influences and celebrated in some nightlife spaces. Despite progress, club owners, promoters, DJs and other positions of influence remain majority male-occupied. Data reveals the prevalence of social and cultural constructions of genre ‘quality’, innate gendered music taste and genre ‘safety’.

Niche EDM is subjectively perceived as a better quality genre than eclectic genres, due to DJ prestige and other factors. Niche EDM is associated with masculinity and some eclectic genres, like pop music, are seen as feminine. Some venues curate ‘female-friendly’ club nights on the assumption that masculine genre nights will lead to violence. This ignores real safety needs such as awareness and anti-harassment training. Sometimes genre, gender and place are connected – for example, ‘masculine’ Berlin techno. When genres travel, gendered standards and assumptions follow. This culminates in static, limited and less critical understandings of femininity and masculinity within genre communities.

How are genre identities and racial identities connected? How does cultural production marginalise genres and minority communities? How do genres become associated with race and how does that racialisation change over time and space? Existing research shows that processes of exclusion based on race, ethnicity and class originate partly from door policies and other access barriers. However, there are more stories to tell. This research looks at the ‘whitening’ process of historically POC genres and cultural narratives, the impacts of economic organisation in racialised genres and the experiences of POC promoters and nightlife patrons in majority white nightlife landscapes.

Genres have cultural histories bound to place and community, but the connection between genre and social group is not fixed and can be lost and/or reassigned when genres travel. House, techno, r&b and hip hop originate from POC communities in American cities. As these genres became popular in the Netherlands, they were absorbed into the majority of music cultures and ‘whitened’. Association with POC genre histories was lost when no connection was made with minority communities in the Netherlands. The ‘colourblind genre’ myth also detaches the genre from any racial association and does not acknowledge local contemporary POC genre scenes.

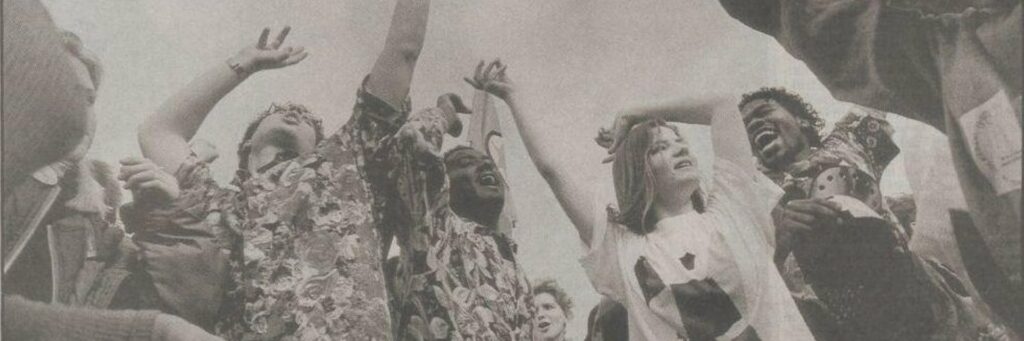

In Amsterdam, while efforts are made to recognise genre histories and integrate local communities, POC and other marginalised promoters face discriminatory barriers. Whiteness is still the ‘invisible norm’ in cultural production, and discriminatory standards can also be adopted from other majority-white scenes. The economic organisation of nightlife in Amsterdam necessitates that club nights are profitable, and many spaces subscribe to a uniform identity. Collectives and parties without permanent venue homes, often with mainly non-white and marginalised audiences, do not fit this model and are excluded from cultural production. Problematic attitudes tying POC audiences to unsafety and increased violence still exist.

This research uncovers the importance of programming and promotion in shaping social and spatial conditions in nightlife spaces and nighttime economies. It centres cultural production on combating discrimination and exclusion in nightlife. While dialogues and concrete steps are being taken, prohibitive stereotypes and other problematic standards remain. Promoters and programmers have the duty to address racial, gender and other barriers and bias in their spaces. This can be accomplished by 1) examining how nightclub production, economic organisation and other norms and standards contribute negatively and 2) engaging directly and inclusively with genre communities. After all, clubbers play a critical role by invoking genre social principles and ideals.

Read the publications from Timo Koren:

Koren, T. (2023) ‘ “They were told it was too Black”: The (re)production of whiteness in Amsterdam-based nightclubs’, Geoforum, [link]

Koren, T. (2022) ‘The work that genre does: How music genre mediates gender inequalities in the informal work cultures of Amsterdam’s nightclubs’, Poetics, [link]