How to address noise complaints and other neighbourhood issues?

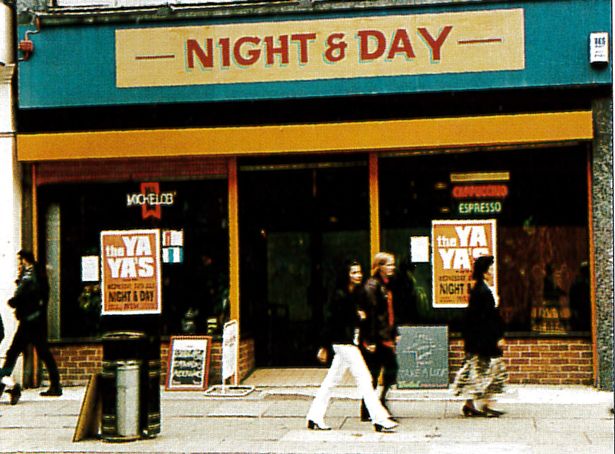

Historical Manchester venue Night & Day 1998

Nightlife scenes and local communities have all the potential to coexist peacefully and productively in the urban environment. Each enriches the other, leading to neighbourhood cohesion, mutual support and social and economic vitality. A city where people, businesses and culture can live, entertain, work and socialise together is a measure of urban economic and social sustainability.

Thriving nightlife districts are those which accommodate and consider residents, as well as invite and attract tourists. Compelling scenes provide platforms for new and innovative artists and maintain ties to neighbourhood traditions. These areas should be safe, functional and fun for all. Urban fabric thrives when urban planning and policy frameworks, zoning regulations and development rules consider residents’ quality of life equal to the commercial and cultural value of nightlife.

Conflicts over the use of urban space:

Unfortunately, conflicts between nightlife spaces, local communities and municipalities do occur. Recurrent quality of life concerns of residents include noise, nuisance and safety. Often, nightlife spaces are attacked by residents and municipalities both for simply providing the entertainment and cultural functions they are meant for. Restrictive curfews, inundation with noise complaints and fines, and unsupervised residential development threaten nightlife spaces and increase tension. Gentrification processes can push out long-standing communities, making way for entertainment districts only accessible to newer, more affluent incoming residents. These same processes can threaten long-standing venues, bars and other nightlife and cultural spaces when new residents do not accept preexisting neighbourhood functions and use. Municipal negligence to these dynamics and runaway real estate development has strained these actors.

When cities do not actively engage with these urban processes, unintended competition and animosity between local residents and businesses can, in the worst cases, lead to venues being forced to shut down under financial burdens. If this trend continues, more and more venues will close, and nightlife districts will lose historic character and vitality. Fortunately, local and international dialogue occurs between nightlife actors and policymakers. Mediation and compromise can be found via both official and unofficial channels. The push for later curfews, and other framework changes, can lead to robust and sustainable nightlife at the same time as livable neighbourhoods.

Agent of change principle:

In many cities, nightlife districts have historically taken root where residential land use is far less common than commercial. Examples include former industrial quarters, river or waterside land and urban core areas that have lost population density due to suburbanisation. This separation of land uses leads to relative peace for nightlife businesses, patrons and local communities. Neither disturbs nor encroaches on the other.

However, as neighbourhoods become increasingly more mixed-use, conflicts arise when existing businesses are burdened with the consequences of incoming residents or vice versa. Noise-generating activities from nightlife, including music and outdoor crowds, may disturb new residents to the degree that official noise complaints are made. Frustrated nightlife businesses are left to contend with resulting fines and a lack of municipal support. One strategy to manage this increasing trend is the agent of change principle.

Essentially, the incoming entity is responsible for mitigating any changes that may occur due to its introduction into a neighbourhood. For example, if a residential apartment block were to be proposed in a nightlife district, the developer must manage the soundproofing of units and other mitigating measures. This would benefit businesses and residents, as neither is forced to deal with a disturbance.

Best practices and priority-setting:

Several nighttime business associations, tourism authorities, different levels of urban to national governments and other nightlife advocacy groups are currently engaging with the topic of “agent of change” and the potential of such measures to mitigate increasing conflicts over noise and nuisance in changing nightlife districts. In this way, best practices and lessons can be shared, leading ideally to the repetition of successes.

In December 2022, representatives from 24 Hour London of the Greater London Authority met with Cansel Kiziltepe, the German Secretary of State, to discuss sustainable 24-hour neighbourhoods where the city centre’s affordable housing construction can coexist with nightlife culture.

The agent of change concept is equally relevant for the construction of affordable housing as for the construction of middle and high-income housing and the conversion of commercial spaces (lofts, etc.) into high-end housing. Led by Night Mayor Robert-Jan Wille, the City of Alkmaar, Netherlands, is conducting location profiling of nightlife businesses, including the quality of soundproofing in nearby residential buildings.

In November 2022, the City of Pittsburgh met with nightlife venues to discuss the agent of change idea and how it can be applied. Also, in the United States, the Nighttime Economy Culture and Policy Alliance (NITE CAP) recently facilitated a gathering of minds on the topic.

In the UK, the Nighttime Industries Association (NTIA) has identified current priorities, including better frameworks for managing noise conflicts, soundproofing and the application of agent of change concepts in the nighttime economy. Nightlife actors understand how essential mitigation is for sustainable nightlife and livable centre city neighbourhoods.

Noise dispute case studies:

More and more venues and nightlife districts come under threat of debilitating fines and

in the worst-case scenario, closure. Complainants are primarily concerned with the noise disturbance from nighttime activities near their residences. Examining a selection of past and present venue case studies illustrates the current state of affairs regarding the agent of change and other creative solutions.

In November 2021, the Manchester Night & Day independent music venue was served with a noise abatement notice from the city council. The venue could be taken to court and closed due to ‘noise nuisance’. The noise complaint originated from a neighbour who had moved in during a pandemic lockdown after the venue reopened. Night & Day opened its stage for emerging artists more than 30 years ago, well before the city council approved the construction of surrounding flats. The venue has already made sound mitigation improvements and meets noise level regulations. They blame the city for not considering existing businesses during housing development and failing to coordinate between municipal departments. Court proceedings will begin in early 2023.

Elsewhere in the UK, Birmingham’s The Nightingale has reached a so-called ‘section 106 agreement’ with developers and the city granting £1.5 million for sound mitigation renovations after a large residential development had been approved ‘in principle’ directly across from the 40-year-old LGBTQIA+ venue. In such agreements, the obligation to lessen community impacts is usually placed on developers. However, in this case, funding for these works has been provided to the venue. On the one hand, the 106 agreement concludes a step forward and an important precedent for defending nightlife districts from new, unregulated residential developments. However, the worry remains because noise complaints can still be filed.

The expenditure by venues in time, legal fees and changes to neighbourhood character still threaten the vitality and survival of nightlife districts. Further examples are seen in the stories of several historical venues in Montreal, all long-standing platforms for emerging artists. Some years ago, Quai des Brumes began receiving noise complaints from a new neighbour who had received permission to convert a commercial space into a residence. The city awarded a subvention to construct sound insulation, which was impossible due to the ageing venue structure. Eventually, Quai des Brumes bought out the neighbour to move. More recently, La Tulipe has also been contending with noise complaints from a neighbour who converted a commercial space next door into a residence. The municipality granted this rezoning permit in error, and the borough government has taken the case to court.

Alternative solutions:

Venues do not stand nor operate alone in these noise and nuisance conflicts. In Manchester, calls for the city council to drop its legal action against Night & Day have come from the city’s music commission and the region’s night-time economy advisor. Close to 100,000 people have signed a petition to drop the abatement notice. City councillors in Birmingham have expressed concern about the impact of new residential development on the longevity of venues such as The Nightingale and the safety of its LGBTQIA+ patrons. Artists who began their careers at such venues, including Matt Healy from The 1975 and Guy Harvey from Elbow (both in the case of Night & Day), have raised their voices against closures.

Attempts are often made to engage directly with surrounding residents in an effort to solve noise conflicts outside of any penal system. Night & Day holds quarterly meetings with local residents to discuss issues of concern. Quai des Brumes and neighbouring venues, including L’Esco and Pow Pow, have called residents directly to discuss noise complaints before they are made to authorities. NTIA encourages members to engage in a ‘360 degree approach’ to communication whereby all businesses, residents and authorities contribute. There is obvious potential for addressing disturbance complaints when the “agent of change” principles are absent or do not apply.

Municipal mediation programs present another option wherein willing participants can problem-solve within their urban communities to avoid costly and unnecessary interference from authorities. The New York City Office of Nightlife has recently launched one such program. MEND (Mediation & Conflict Resolution Program) is a citywide initiative and non-punitive and voluntary mediation program offered to residents and nightlife businesses. MEND is available for disputes between residents and venues, neighbouring venues, and commercial landlords. The program has recently mediated approximately 80 cases with a roughly 80% success rate.