Intentional archiving of club culture and heritage

Club culture’s global influence is undeniable, yet it still struggles for legitimacy. Despite being the driving force behind nighttime economies and the laboratory for progressive visions of the future, it often remains sidelined by institutions when it comes to recognising club culture’s role in shaping society and contributing to public heritage.

Club cultural history is sprawling yet fragile, told through fragmented oral traditions, vanishing dancefloors, and the selective memory of mainstream media. Intentional archival — and not mere documentation — is crucial for legitimising and protecting dance music as a cultural form.

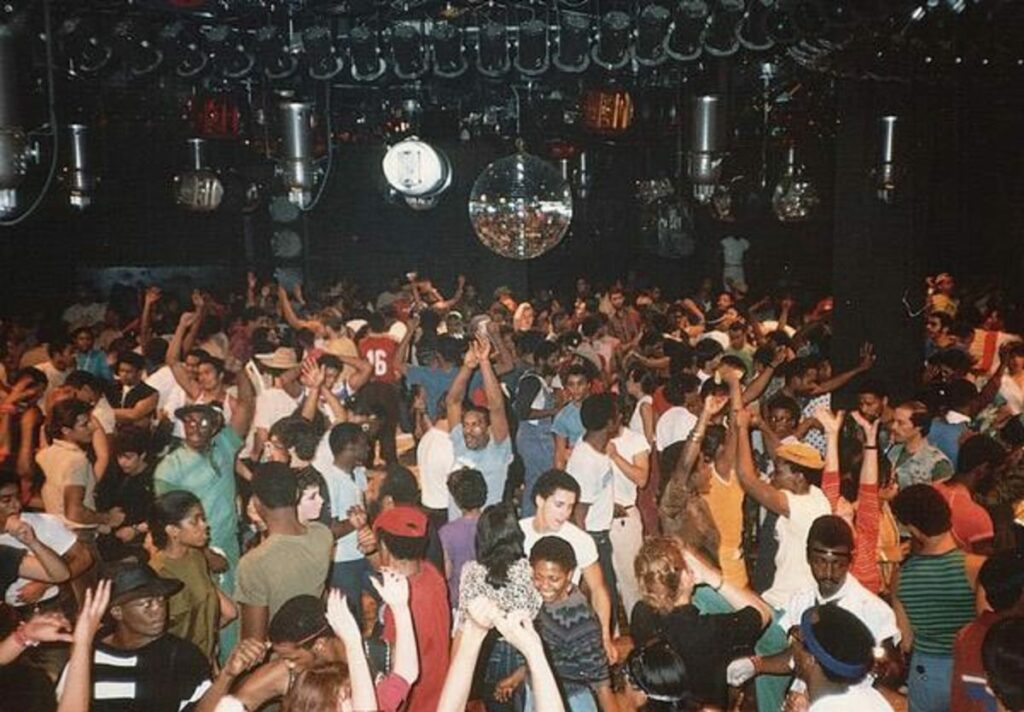

Unlike rock’s meticulously archived and endlessly repackaged mythology, dance music’s legacy remains precariously scattered, its history fading with each disappearing dancefloor. Nightlife is a space for experimentation and subversion, but what happens at night usually stays there. Beyond the underground networks, dance music culture is seeing the systemic erasure of the Black, queer, and working-class pioneers who built it. The industry cherry-picks its icons while entire movements are passed over, their stories shared in afterparty conversations rather than preserved in public memory.

The legendary status of nightclubs like Paradise Garage in New York are the exception, not the norm in the broader cultural archive. Credits: photographer and source unknown.

The dance music world has always been good at documentation. Obsessive crate digging is matched by exhaustive collections of flyers, radio rips, grainy phone footage. Today, the commercial success of coffee table-format heritage for club culture enthusiasts is driven by collectibles such as the recently published book by legendary Brussels club Fuse, and John Leo Gillen’s book Temporary Pleasures on the history of nightclub architecture. Club culture has also received recognition beyond consumer tastes and collaborations with high art— most notably with Germany’s inclusion of Berlin’s techno scene in UNESCO’s list of intangible cultural heritage. Even outside of Western contexts, indigenous electronic dance music is being re-discovered and celebrated. In Indonesia, Funkot’s international and domestic success is acknowledging the genre beyond comparisons to gabber, a genre from the country’s former coloniser. In India, Charanjit Singh’s Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat is finally being reclaimed as a homegrown progenitor of acid house.

A cover by band Glass Beams of Raga Bhairav (1982) by Charanjit Singh, which is now celebrated in India as a homegrown pioneer of acid house.

But as Emma Warren puts it in Document Your Culture, “Documenting is the act of capturing information, while archiving is about preserving and organizing that information for the future.” Archiving requires intention. Without it, documenting dance music becomes an exercise in exploiting and gatekeeping culture. Without actively supporting the culture and communities that keep these legacies alive, history becomes a conversation piece, a fashion statement. We risk being too busy pontificating to remember to dance. In a recent article, Chal Ravens describes this tendency of ‘academisation’ and ‘museum-ification’ which has “turned the dancefloor into a kind of ideological zone of contestation rather than just a receptacle for weekend hedonism”. While this shift reflects dance music’s cultural importance, it also risks detaching it from the communities that built it. Although politics on and off the dancefloor is a laudable progression, dance music history should not be merely appropriated for the tastes of highbrow art. In our scramble to turn our passions to side-hustles and our art into content, are we losing the intangible and ephemeral experience of the night? Ravens warns that “the now late-onset celebration of rave doesn’t also serve as its eulogy”. Without intention, history is left to be rewritten by those who can afford to control the narrative.

Archiving should instead serve to strengthen and advocate for the communities at the heart of nightlife and club culture. VibeLab in collaboration with Podiumkunst.net are undertaking a project ‘Archiving Dutch Club Culture’ that aims to empower and give voice to the hidden stories of grassroots creative communities in the Netherlands. The goal is to develop a living archive that is sustainable and community-run. Senior project manager at VibeLab Thomas Scheele emphasises that “our goal is not just to collect stories, but to empower communities to document and preserve their own heritage.” The project was well received at the recent Dancecult Research Network Conference held in Berlin in January 2025, where the team presented the project’s results. Work such as this shows that intentional archiving is not just about preserving the past—it is about empowering communities to shape how their histories are told. If dance music is to resist erasure, its archiving must be a living, participatory act, driven by the very people who sustain its culture.

In July, VibeLab in collaboration with Podiumkunst.net published the report “Archiving Dutch Night and Club Culture”, which explores how nightlife communities, artists and institutions in the Netherlands are documenting and safeguarding club culture history. The report includes case studies, stakeholder insights and practical tools for grassroots communities to document their own culture. Recommendations will be shared with cultural institutions and city officials later this year. The report is available online for free download in English and Dutch.